⚡️ TL;DR

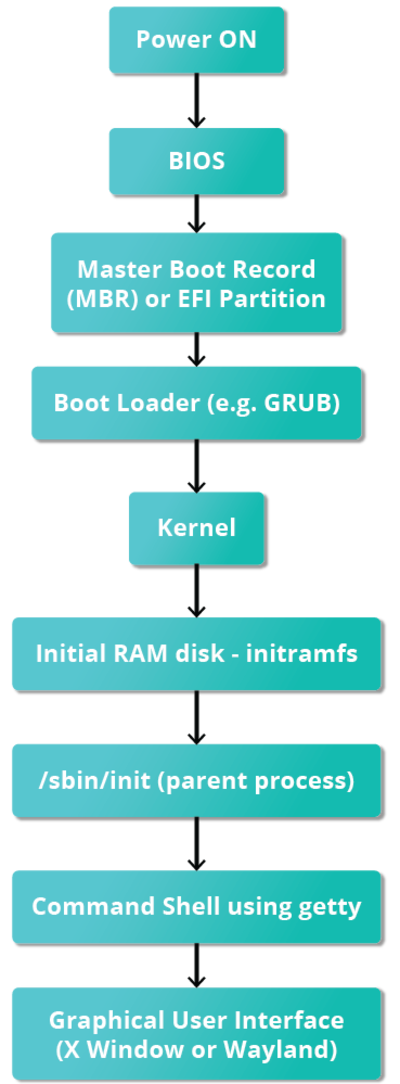

Understanding the Linux boot process is crucial for anyone diving into the world of Linux. It’s the sequence that kicks off when you power on your computer, leading up to a fully operational user interface. Grasping this process can enhance your troubleshooting skills and help you fine-tune your system’s performance to fit your needs. While it can seem technical, fear not—you can start using Linux without diving deep into every detail.

The Boot Process: A High-Level Overview

BIOS: The First Step

Let’s begin with the Basic Input/Output System (BIOS), the unsung hero of the startup. This firmware initializes your hardware—like the keyboard and screen—and performs a Power On Self Test (POST) to check your system’s memory. This part of the process happens before your Linux operating system takes the reins.

The BIOS is stored on a read-only memory (ROM) chip on the motherboard, and once it completes POST, it hands control over to the boot loader. This transition is critical, as it sets the stage for the next steps in the boot process.

Boot Loader: The Next Stage

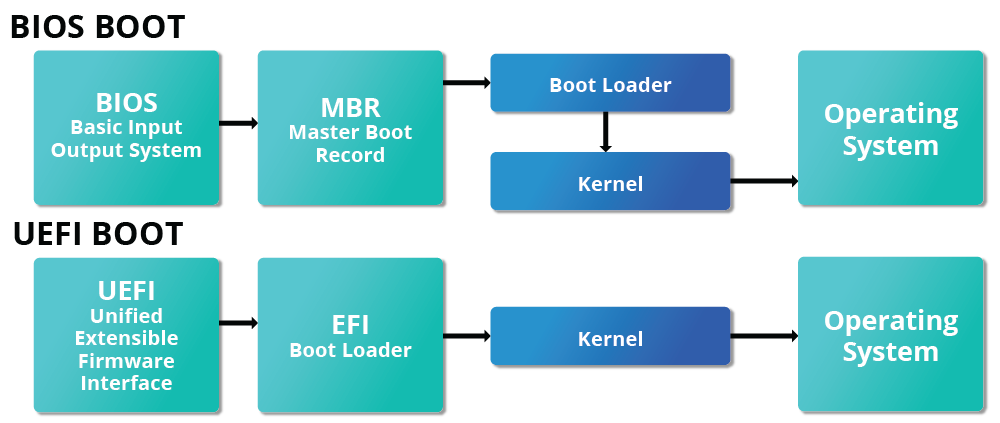

Once POST is complete, the boot loader takes over. This component is typically found on your hard disk or SSD, either in the Master Boot Record (MBR) for traditional systems or in the EFI partition for newer EFI/UEFI systems. At this point, the system doesn’t access any mass storage media yet. Instead, it pulls date, time, and peripheral information from the CMOS values.

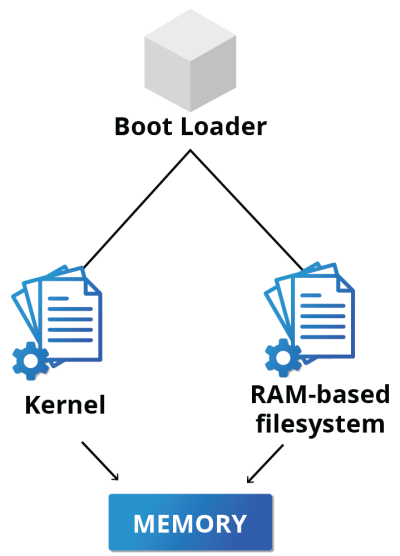

The boot loader plays a pivotal role in this process. Common examples include GRUB (the GRand Unified Bootloader), ISOLINUX (for removable media), and DAS U-Boot (for embedded devices). The boot loader loads the kernel image and the initial RAM disk into memory, preparing the system for the next phase.

The boot loader functions in two distinct stages. In BIOS/MBR systems, it resides in the first sector of the hard disk. This small 512-byte MBR checks the partition table for a bootable partition. Once found, it loads the second stage boot loader, like GRUB, into RAM.

For EFI/UEFI systems, the process is a bit more complex. The UEFI firmware reads Boot Manager data to determine which UEFI application to launch, adding a layer of versatility compared to the older MBR method.

After the OS and kernel are selected, the boot loader loads the kernel into RAM, which is typically compressed. The first task of the kernel? Uncompress itself and configure the system hardware, including drivers for attached devices.

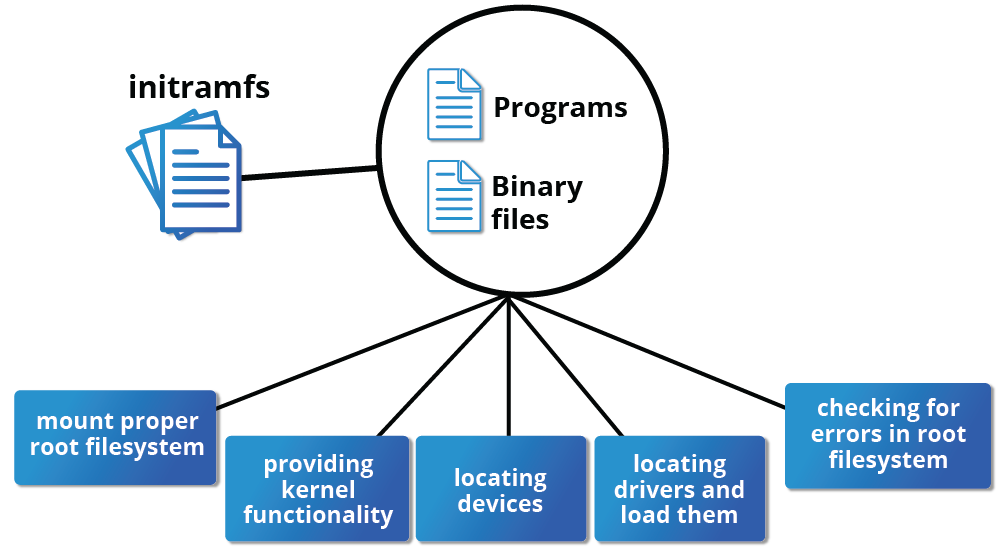

The Initial RAM Filesystem (initramfs)

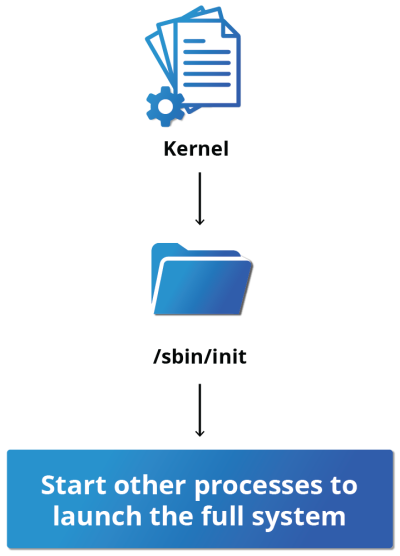

Once the kernel is up and running, it interacts with the initial RAM disk (initrd) or initial RAM filesystem (initramfs). This image contains programs necessary for mounting the root filesystem, including drivers for mass storage controllers. The initramfs handles the mounting process, and upon success, it clears itself from RAM, passing control to the init process located at /sbin/init.

The init process takes it from here, handling the transition to the real root filesystem. If special drivers are required before mass storage is accessible, they reside in the initramfs.

Text Mode Login

As the boot process nears its end, the system presents text-mode login prompts. Here, you can enter your username and password to access the command shell. If you’re using a graphical interface, you might not see these prompts initially.

Linux systems usually start six text terminals and one graphical terminal, accessible through the function keys + ALT key. The default shell is often bash, ready to accept your commands.

Kernel initialization

The kernel is the heart of the Linux operating system. Once loaded into RAM, it initializes memory and configures all hardware. The kernel also loads necessary user-space applications.

After the kernel sets everything up, it runs /sbin/init, becoming the initial process. From here, init manages other processes, ensuring everything runs smoothly. It handles service management—cleaning up after processes and managing user logins.

Traditionally, system initialization followed a sequential method called SysVinit, where runlevels determined service states. However, most distributions have transitioned away from this method in favor of more modern alternatives like systemd.

The SysVinit method, while historically significant, lacked efficiency, especially on modern multi-core processors. It treated startup as a series of steps, often leading to longer boot times—something we can’t afford in today’s fast-paced world.

Enter systemd. Adopted by major distributions like Fedora and RHEL, systemd brought a revolution in how we handle system initialization. It allows for faster startups through parallel processing and replaces complex scripts with simple configuration files.

With systemd, you can use the systemctl command for managing services easily. Want to start the Apache web server? Just run:

1sudo systemctl start httpd.service

Linux Filesystem Basics

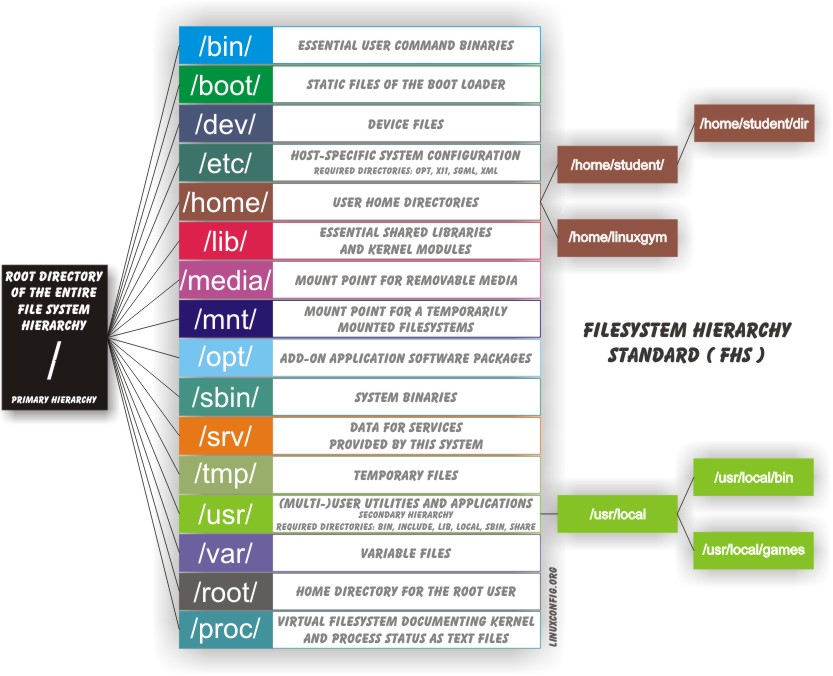

Linux filesystems are where the magic happens. They provide a method for storing and organizing your data. Think of filesystems like library sections, categorized for easy retrieval. Linux supports various types of filesystems, including ext4, XFS, and special-purpose filesystems like procfs and sysfs.

A partition is essentially a designated area of storage media. While Linux can handle multiple partitions, the filesystem is what organizes the files within those partitions. Each Linux filesystem is case-sensitive, meaning /boot, /Boot, and /BOOT are treated as distinct directories.

One can think of a partition as a container in which a filesystem resides. However, in some circumstances, a filesystem can span more than one partition if one uses symbolic links, which we will discuss much later.

Make a table comparison between filesystems in Windows and Linux.

| WINDOWS | LINUX | |

|---|---|---|

| Partition | Disk1, Disk2, etc. |

/dev/sda1, /dev/sdb1, etc. |

| Filesystem | NTFS, FAT32, exFAT |

ext3, ext4, XFS, Btrfs, etc. |

| Mount point | C:, D:, etc. |

/, /home, /var, etc. |

| Base folder | C:\ |

/ |

| Path separator | \ |

/ |

To maintain consistency, Linux adheres to the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS), which dictates where files are stored. Unlike Windows, Linux uses a single filesystem structure without drive letters. For instance, removable media might be mounted at /media or /mnt.

Linux uses the / character to separate paths (as sis UNIX unlike Windows, which uses \) and does not have drive letters. Multiple drives and/or partitions are mounted as directories in the single filesystem. Removable media such as USB drives and CDs, and DVDs will show up as mounted at /run/media/yourusername/disklabel for recent Linux systems or under /media for older distributions. For example, if your username is student, a USB pen drive labeled FEDORA might end up being found at /run/media/student/FEDORA, and a file README.txt on that disc would be at /run/media/student/FEDORA/README.txt.

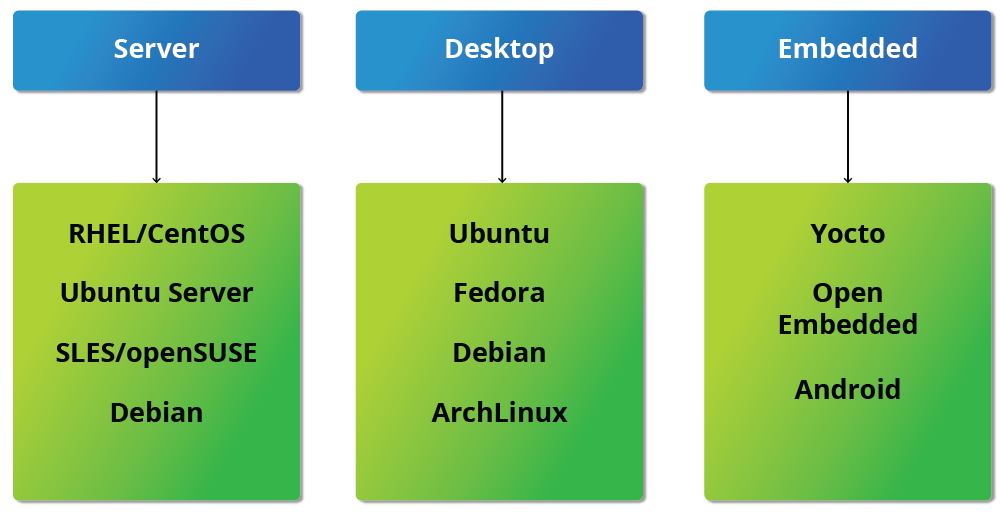

Determining the Linux Distribution

Determining which Linux distribution to deploy requires thoughtful planning. The partition layout is best decided at the time of installation.

Most installers set up some initial security features on the new system, such as setting the password for the superuser root and setting up an initial user.

Modern distributions simplify the installation process by allowing users to make software choices after the initial setup, reducing intimidation for new users compared to older methods that required numerous decisions upfront. Stay tuned for more in-depth discussions on Linux distributions in future posts.